For Kelly Crago, life has come full circle. From childhood days riding in tractors on her family’s farm in Marchagee to working major crime cases in Perth, she now finds herself once again under country skies, this time with a baby on her hip and a sewing machine at her side.

“I had the ideal farm kid life,” she says. “Being the eldest of four siblings, my farm apprenticeship started early. I’d steer the old ute along fence lines while Dad threw out star pickets. I couldn’t imagine doing anything but farming.”

But at 16, life took a sharp turn. Her parents separated, and her mum moved the family to Perth. “The cultural shift was dramatic,” she recalls. “We lost touch with our community, our friends, and a lot of our dad’s side of the family. At the time, teenage misadventure distracted me from farming dreams, but the impact on my confidence and identity lasted a long time.”

After school, university was off the table. Kelly was unqualified, low on funds, and still caring for a few horses. A contract job as a stable hand at the Mounted Police Unit introduced her to a steady income and eventually led to her enrolling as a police recruit.

“I remember someone telling me the Police Commissioner expected seven years of service from officers. That stuck with me, ‘you’re a failure if you bail out before seven.’ So, I stayed for eleven.”

Kelly rose through the ranks, eventually becoming a detective working in the Perth CBD. She investigated crimes from child abuse to homicide. The job was demanding, emotionally complex, and exposed her to the raw edges of society.

“One case really stuck with me, a young child had died, and we were investigating the family. Four generations of neglect, drug use, unemployment. It made me realise it’s possible to detest someone’s actions while still feeling sorrow for how they got there.”

Another moment came during a tactical training exercise after she’d transferred to the Wheatbelt. “I told a colleague I was moving to take cover behind a Kurrajong. They had no idea what I was talking about so I had to rephrase, ‘smooth tree with grey bark.’ I hadn’t realised how foreign those terms were outside country life.”

Despite tough moments, she credits her time in the force with shaping her communication skills and emotional resilience. “Conflict was my bread and butter. I dealt with it every day, and I learnt that good communication can resolve most problems, whether with a colleague or in the community.”

Being a woman in law enforcement brought its own challenges. Kelly remembers a supervisor early in her career who consistently undermined her. “I didn’t realise at the time that his treatment was unusual. I just tried to keep smiling. Thankfully, a female sergeant saw what was going on and quietly made sure I ended up on her team. Her support made all the difference.”

She also dealt with late-night messages from senior male colleagues. “A firm ‘how’s your wife?’ usually did the trick. I didn’t see the point in ruining someone’s life or career over a poor decision if I could handle it with clear boundaries.”

Eventually, her passion for policing began to wane.

“I’ve always said I’d never raise my kids in the city. That resolution kept me grounded through a lot of personal ups and downs. I had served my seven years, but then I’d trained as a detective, was close to permanency. It felt like quitting would waste all that effort.”

Then she saw a poster at work listing logical fallacies. One caught her eye, the Sunk Cost Fallacy. “It’s when you stick with something just because you’ve invested in it, even if it’s no longer right. That hit me hard. Soon after, I applied to transfer to Moora Police Station.”

The move home let her reconnect with farm life and gradually prepare for full-time agriculture. But country policing came with its own frustrations.

“Working in a small town meant constantly being called out, often for petty disputes. It wore me down. Occasionally there were meaningful moments, someone truly in need, but I realised I was out of steam.”

She formally began working on the family farm part-time and eventually resigned in November 2023 to return to farming full-time. The shift brought fresh challenges, including isolation and the leap from a structured government role to a family-run business.

Now, with a baby daughter and two stepsons, Kelly’s focus has shifted again. While being at home with a newborn, she turned to a lifelong hobby; sewing.

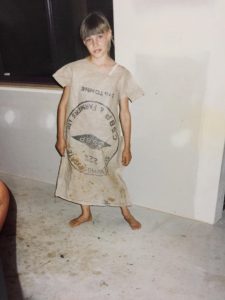

“I’m tall and have always struggled to find clothes that fit, so I learnt to sew young. There’s an old photo of me wearing a dress I made from a fertiliser bag to climb trees in. My style has improved since then.”

“I’m tall and have always struggled to find clothes that fit, so I learnt to sew young. There’s an old photo of me wearing a dress I made from a fertiliser bag to climb trees in. My style has improved since then.”

What began as hand towel gifts for family grew into a market stall and website: The Modest Modiste. She sews from home, with a baby monitor beside her and a strong belief in maintaining quality over quantity.

“I’m not interested in churning out cheap things just to sell. I want to make things that are beautiful, useful, and well made.”

Though she’s still learning the ins and outs of small business, like linking her website to social media, filming behind-the-scenes reels, and navigating market trends, she’s committed. “Calling myself a small business owner makes me seem more successful than I am, but I love the creativity and the connection it brings.”

Juggling motherhood, business and life on the farm takes flexibility and grace.

“I’ve had to let go of strict to-do lists. If bub is fussy, nothing might get done. I’ve learned to take wins where I can. The housework can wait.”

Community support has helped. “Moora is a great little town. Most people I’ve run into have been really encouraging about this new chapter.”

Looking back, Kelly is proud of many things. “Becoming a mum is definitely up there. But I’m also proud of choosing a life that makes me happy. It would have been easy to stay in the city, keep climbing the ladder, but I wanted something more grounded.”

To other women considering a big change or a return to the regions, her advice is simple: “Look at your core values and make choices that match. Don’t let fear or logistics keep you from your dream. I thought leaving the farm meant the door was closed. Turns out, I was wrong. Ag has always been here. There’s plenty of room for everyone.”

Life on the land now feels like home, but if she had the chance to sit around the firepit and share stories with a few special people, her guest list would be deeply personal:

“My partner’s father, John Tonkin. He died before I was on the scene and by all accounts was a great bloke. My Pop, Percy Crago, gets an invite as well. He went too soon and didn’t get to meet my kids. And there’s a place for Jacinta Price. She’s got lots to say on topics I’m interested in and I love her brutally honest perspective.”